Former guards paint bleak picture of conditions inside notorious immigrant detention center in Baker County

Conditions at the Baker County ICE Detention Center in rural northeast Florida, where more than 200 immigrants are detained, have been abysmal and at times horrific for years, according to numerous complaints.

Immigrants there awaiting court hearings and sometimes deportation have alleged unsanitary conditions, physical abuse and denial of medical care, legal counsel and sufficient food rations, according to the ACLU of Florida, which filed a lawsuit on their behalf in September 2022. The ACLU also joined with 16 other civil rights groups to lodge a 22-page complaint with the Department of Homeland Security regarding the “intolerable” conditions at the center.

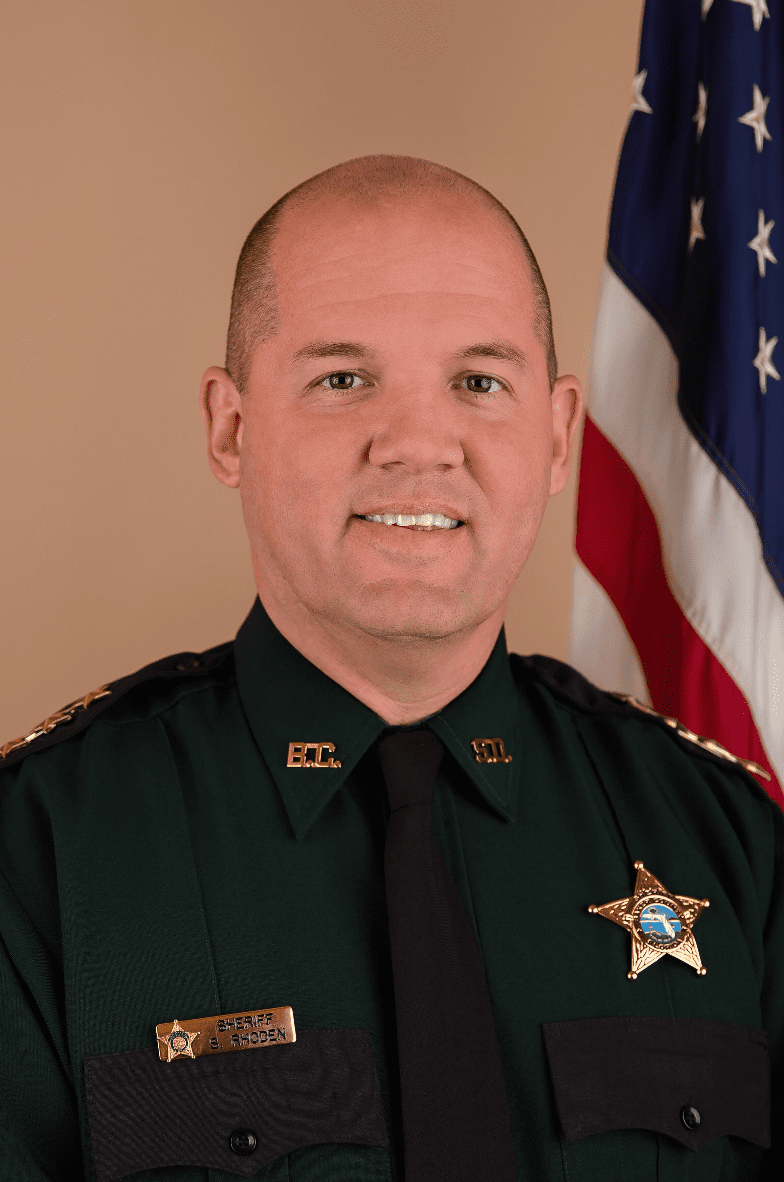

It’s not just detainees who tell of terrible treatment at the detention center, which is run by the Baker County Sheriff’s Office. Two former guards at the facility, who spoke to the Florida Trident on condition of anonymity, said they witnessed – and experienced – substandard conditions as well. Both claim the facility is mismanaged by Baker Sheriff Scotty Rhoden, who’s named in the ACLU lawsuit and is also the subject of an ongoing and apparently unrelated criminal investigation by the Florida Department of Law Enforcement. The complaint filed with DHS urged the termination of ICE’s contract with Baker County, calling the latter an “unfit partner by any metric.”

Rhoden refused to discuss specific allegations regarding the facility, citing the lawsuit. When asked if there had been a history of civil and human rights violations—abuse, racism and retaliation—in the detention center, the sheriff replied, “No, there has not.”

(Courtesy: Baker County Sheriff’s Officer)

The guards dispute that. One said conditions are so awful that detainees turn to a “frequently used last resort”: hunger strikes.

“After so many, you get used to it,” the former corrections officer said of the hunger strikes. “It’s not uncommon. I’ve seen people not eat and are serious about it, and I’ve seen them wither away.”

The ex-guard said one popular method used at the Baker ICE center to end the strikes, and collectively punish the detainees, was particularly inhumane and degrading: shutting off all running water in the facility.

The guard said when the master valve was closed, every faucet and shower in the facility went dry and every toilet was unflushable, affecting inmates in the entire housing area and creating unsanitary conditions. The alleged reason for BCSO’s water shutdown was to measure water intake during the strike, but the former corrections officer said the real reason for the administered droughts was to break morale.

These reports from staff correspond with a claim in the ACLU lawsuit describing a large hunger strike involving more than 100 inmates in May 2022. BCSO initially threatened to shut off all access to water if the strike commenced, and when it did, the agency followed through on the threat.

“It was basically forcing their hands to end the hunger strike,” Amy Godshall, an attorney with the ACLU, told the Trident. “Guards instigate things like that and have the people detained there to turn on each other. It’s psychological warfare.”

The lawsuit appears to be headed to trial after a settlement mediation period expired July 15 with no agreement reached between the parties.

“After we started speaking about the facility, the sheriff and undersheriff displayed animosity against us and those who also spoke out,” Godshall said. “We have heard from a lot of people who are scared to talk to us, because they are scared of retaliation. There are always officers around to overhear the conversation about the conditions, and so the ones who control the conditions are standing right next to them.”

On patrol through the facility

Both of the former BCSO corrections officers paint a dark portrait of the Baker County Ice Detention Center, not just for the inmates but also for the guards.

“The cells, the dorms, the housing areas—it’s all pretty bad,” said one of them.

Unlike the two other ICE-commissioned detention centers in Florida, the Baker County facility is operated by the sheriff’s office and includes the county jail with general population inmates. The county arrestees are housed in the “A” block while the migrants are detained in the “B” block. Correctional officers rotate and work both sides of the jail, sometimes on the same shift.

Working a shift is a long, lonely job, said the ex-guards. Cell blocks A and B are often patrolled by only one guard each, they said, and calling for assistance usually means crickets, they said.

Guards work 12-hour shifts without any formal breaks, according to the former officers, and the mental toll of “always being on guard” creates strained daily working conditions. One of the former officers said they once worked two weeks of 12-hour shifts without a day off. Turnover is high, the guards said.

“You were honestly unable to have any personal relationships due to never being off, and the few days we were off, we were trying to recover and get ready to do it all over again,” one said.

The scarcity of days off from working 12-hour shifts led to the ironic dynamic of the guards themselves feeling incarcerated.

“It was mentally stressful due to having kids that need daycare and not being able to see them,” one said. “It’s not fair that the children of the employees have to be punished because of the administration.”

“They’d constantly call and mandate me to come to work or threaten myself and others with termination,” said the other. “Personal relationships were impacted because you could never make plans with your family due to the possibility of having to work on your day off.”

The former officers said that while Sheriff Rhoden was largely absent and had “no idea what’s going on in the jail,” his undersheriff, Randy Crews, had taken the main leadership role there. Also a defendant in the ACLU’s lawsuit, Crews, like his boss, declined to discuss the facility conditions in detail when reached by the Trident.

“Quite frankly, we’re not really allowed to talk about it per the advice of our attorneys,” he said. “I am not going to go down any rabbit hole of answering any questions about anything to do with immigration or ICE. I am not going to answer questions related to that, no matter what they are.”

The other side of the bars

Inmates like 44-year-old Bobbeth Morgan from Kingston, Jamaica, have alleged terrible conditions inside the facility.

“What I was faced with at Baker County Detention Center sent me down on my knees begging God for mercy,” Morgan wrote in 2022. “The cell was so dirty it had multiple centipedes crawling around and the bunk and walls had blood stains all over. I cried asking God to please work a miracle and wake me up from this nightmare.”

Morgan was instead awoken in the middle of the night by a sergeant sneaking into the jail cell to take photos of her and her cellmate sleeping, she claimed.

Morgan’s letter has been one voice in an ongoing clamor of human rights complaints coming from Baker the past decade: physical and mental abuse, medical neglect, sexual voyeurism, unclean water, no running water, prevalent racism, and retaliation when detainees speak out.

“Baker has grown infamous among immigrants: ‘Do whatever you can to not get transferred to Baker,’” said Katie Blankenship, a former ACLU attorney representing the plaintiffs pro bono. “It is well-known that Baker is the hellhole that it is.”

Detainee testimonies obtained for the lawsuit point toward a cycle of abuse, racism and retaliation. One immigrant was allegedly beaten, handcuffed, sexually assaulted and called a “porch monkey” simply for asking the air conditioning to be adjusted.

Both former officers said they were appalled by the overuse of solitary confinement, where detainees are kept in small enclosures with no windows, and human interaction is limited to when meals are passed through a flap.

County inmates, migrant detainees and state hospital patients go in and out of solitary like a “revolving door,” they said, adding that some remained in isolation for more than a year. Those confined in solidarity often don’t receive recreation time, and while they do have access to a tablet, they often receive only limited access to the legal phones, they said.

“Could you imagine being in there? It’s got to cause you to go crazy,” said the former officer.