Florida ethics bill will protect wrongdoing officials, keep public in the dark

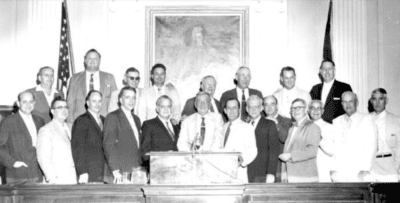

The rural lawmakers who once misruled Florida’s Legislature are remembered for how stoutly they resisted a new constitution, desegregation, lobbyist disclosure and fair representation.

But at least the Pork Choppers, as they were called, never tried to turn back the calendar and repeal progress, which is what Florida’s purportedly modern Legislature brazenly did this month. They also showed more respect for the bedrock American principle of separation of church and state.

The Legislature this year set a benchmark for spiteful, arrogant and destructive legislation when it voted to effectively cripple the Florida Commission on Ethics, along with similar boards in Jacksonville, Tallahassee, Miami-Dade, Naples, Coral Gables, Palm Beach County and Tampa.

The state ethics commission – one of the great reforms of the post-Pork Chop era – is cemented into the Constitution. Its opponents couldn’t simply abolish it without a vote of the people. So, they did the next worst thing by passing a bill that requires citizens who file complaints under oath to have “personal knowledge or information other than hearsay” about the offense they’re reporting.

They also extended that rule to Florida’s several local ethics commissions, which would cripple them too. As Jose Arrojo, the executive director of the Miami-Dade Commission on Ethics and Public Trust, explained it to the Miami Herald, “No more anonymous whistleblowers. No more employees referring information to us. We would be sitting on our hands unless someone comes forward and files a complaint under oath.”

In the process of enacting that one bill (CS/SB 7014), the Legislature displayed three of its worst tendencies:

–Restricting what the public is allowed to know about what their governments are or aren’t doing.

–Erasing local home rule, another post-Porkchop reform, by restricting or banning what locally elected governments can do.

–Passing bills in sneaky ways that conceal bad intentions until nearly the last minute. The Legislature appreciates due process only when it is applied to executive branch agencies.

As it came out of Senate’s Ethics and Elections Committee chaired by Sen. Danny Burgess (R-Zephyrhills), the bill consisted primarily of new procedural rules for the state commission.

Though somewhat burdensome, the new rules are defensible as due process. One of the more substantive of them requires a supermajority vote of commissioners to “reject or deviate” from its own legal counsel’s advice. This is significant because the commission has on occasion insisted on pursuing cases that its legal advisers, who work for the attorney general, said it should drop.

The new rules weren’t particularly controversial. It wasn’t until the day before the full Senate was to take up the bill that Burgess filed an amendment to require that all complaints be based on “personal knowledge or information other than hearsay.” Senate rules allow such short notice and do not require that amendments be previewed by the committees responsible for legislation.

Burgess also filed a floor amendment to let public officials who are lawyers conceal potential conflicts of interest by claiming lawyer-client confidentiality to withhold the names of people whom they would otherwise have to identify on their financial disclosure forms. Without knowing who those people are, it would be impossible for anyone else to know whether something is unethical in the relationship.

The Senate accepted those destructive amendments by voice votes and passed the bill the following day by a vote of 39-0 despite concerns expressed by several senators. Even after the media and local ethics boards blew the whistle, there were only four Senate votes against it on final passage. The final House vote was 79-34. In both chambers, only Democrats voted no or attempted to defang it.

It was obvious Speaker Paul Renner (R-Palm Coast) and Senate President Kathleen Passidomo were in on the scheme. Here’s what Passidomo (R-Naples) told the Miami Herald :

“I believe that state and local ethics boards should be able to spend their time investigating serious violations of our ethics laws, not politically motivated public relations stunts designed to generate headlines. All too often the current process is weaponized by bad actors.”

Throughout, however, no legislator ventured even one example of how the state or local ethics agencies had done any of what Passidomo was talking about. The assault on the ethics commissions sabotaged one of the most significant legacies of Gov. Reubin Askew, who diagnosed waning public confidence as a serious problem. He repeatedly challenged the Legislature to “earn once again the faith of the people.”

In 1969, even the newly reapportioned Legislature had laughed down the idea of an ethics commission. Five years later, Askew hounded them until they not only created a commission but also provided for limited financial disclosure by public officials.

Disclosure was so unwelcome that it attracted 111 amendments in the House. To make disclosure and the commission safe from future legislation, Askew in 1976 sponsored Florida’s first successful petition-initiative campaign to amend the Constitution.

But the 1974 session hobbled the commission by allowing it to act only on sworn complaints from others. From the outset, the commission tried year after year to get the Legislature to let it initiate its own probes and finally gave up trying.

The local ethics boards had no such limit. They will now, if Governor Ron DeSantis doesn’t veto CS/SB 7014

Integrity Florida and The Florida Ethics Institute are submitting a round-robin letter urging DeSantis to veto what they describe as a “profound change in favor of shielding ethics violators from investigative scrutiny.”

Speaking personally, Ben Wilcox, co-founder of Integrity Florida, called it “certainly the worst day for ethics in Tallahassee in probably forever.”

It was a disgraceful conclusion for a session that had deserved praise for shelving a second attempt at making it easier for politicians to sue whistleblowers and the media. Among other things, that bill would have legalized damages for “false light,” a concept the Florida Supreme Court had rejected. “False light” is a snide way of saying truth isn’t a defense for libel. Three House committees had approved that bill but it died on the House calendar. Conservative as well as liberal voices had raised enough of a ruckus to make it radioactive.

In yet another putdown of accountability—and of local voters—the Legislature also outlawed civilian police review boards (HB 601). That was a payback to police unions that customarily favor Republican candidates and are close to Gov. DeSantis. The bill bars any civilian oversight or investigation of complaints against law enforcement and correctional officers. There wasn’t even a single vote against it in the Senate. The House passed it on party lines, with Democrats voting against it.

Another bill (HB 931) that would have embarrassed even the Pork Choppers authorizes untrained volunteer chaplains in public schools if they were approved by county and charter school governing boards. There are no guardrails on who these chaplains might be other than criminal background checks.

The boards can expect heavy pressure from religious groups to allow what is clearly an unconstitutional violation of the First Amendment. They should just say no.